| Treatment Options | Many spinal conditions respond well to surgical treatment. In properly selected patients, surgery provides relief of symptoms, returns function, halts neurological damage, and achieves or restores spinal stability for most patients. At the Spine Hospital at the Neurological Institute of New York, we pride ourselves on providing our patients with clear explanations and the best possible surgical outcomes. The highly trained neurosurgeons in our practice continue a long tradition of expertise, skill, and care, which consistently places them among the top neurosurgeons in the country.

However, surgery is not the treatment of choice for every patient with every condition. The experienced neurosurgeons at The Spine Hospital at the Neurological Institute evaluate each case individually and will tailor a nonsurgical or surgical treatment plan to each patient. To read more about a particular condition and its general treatment options, have a look at our conditions pages.

|

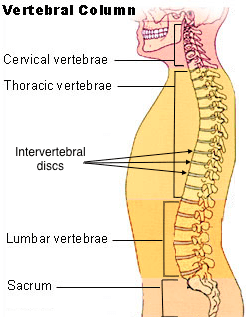

| Spinal Anatomy | To understand how problems of the spine are treated surgically, it helps to understand the structure of the normal spine.

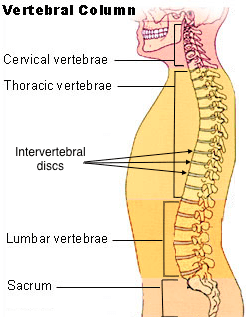

The spine is composed of many vertebrae, or individual bones of the spine, stacked one on top of another. Together, this stack forms the vertebral column. The topmost section of the vertebral column, the section in the neck, is called the cervical spine. The next section, located in the upper and mid-back, is called the thoracic spine. Below the thoracic spine is the lumbar spine, in the lower back. Finally, the sacral spine (or sacrum) is located below the small of the back, between the hips. Sturdy intervertebral discs connect the vertebrae. The intervertebral discs act as cushions and shock absorbers between the vertebrae. Each disc is composed of a jelly-like core surrounded by a fibrous outer ring.

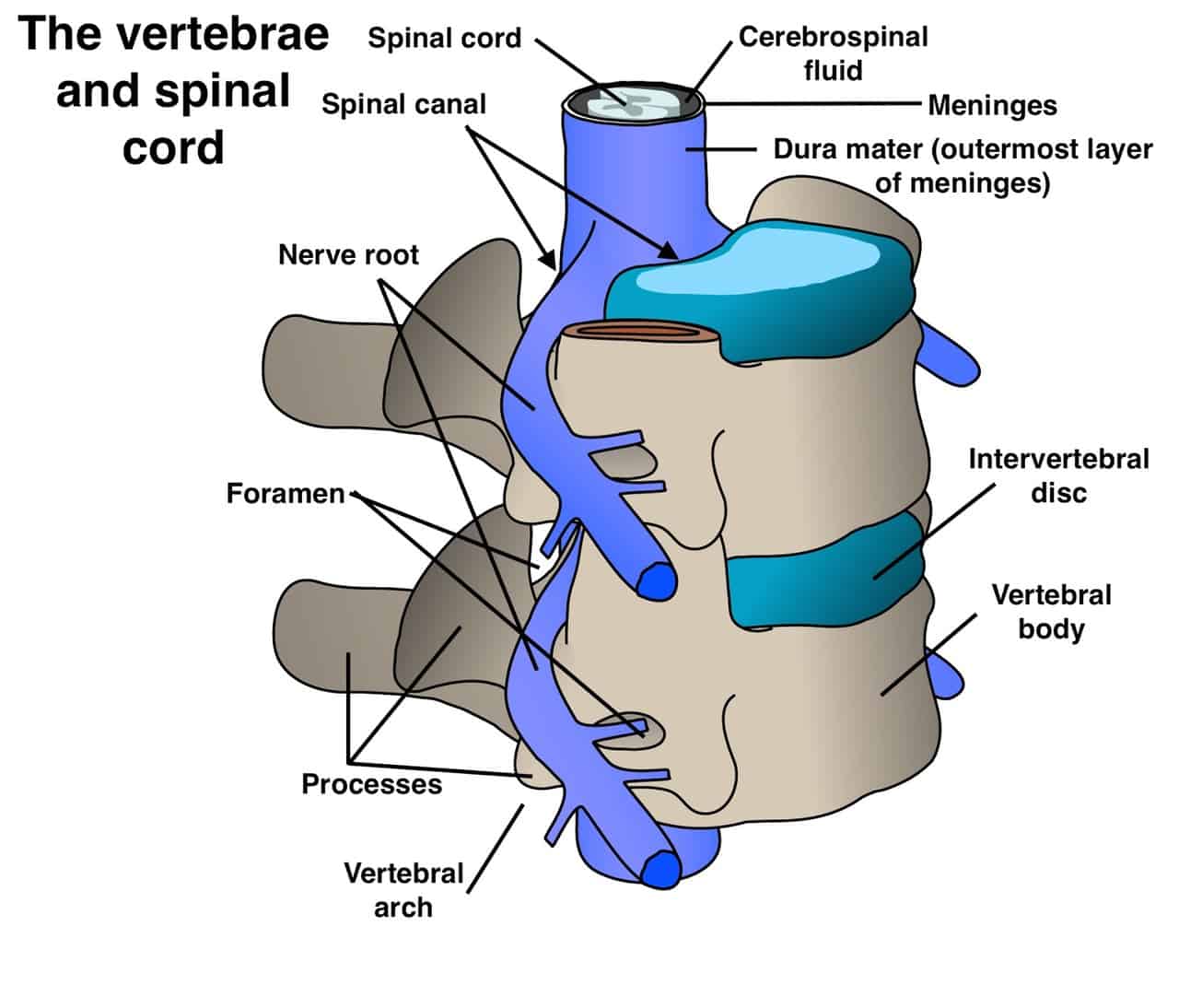

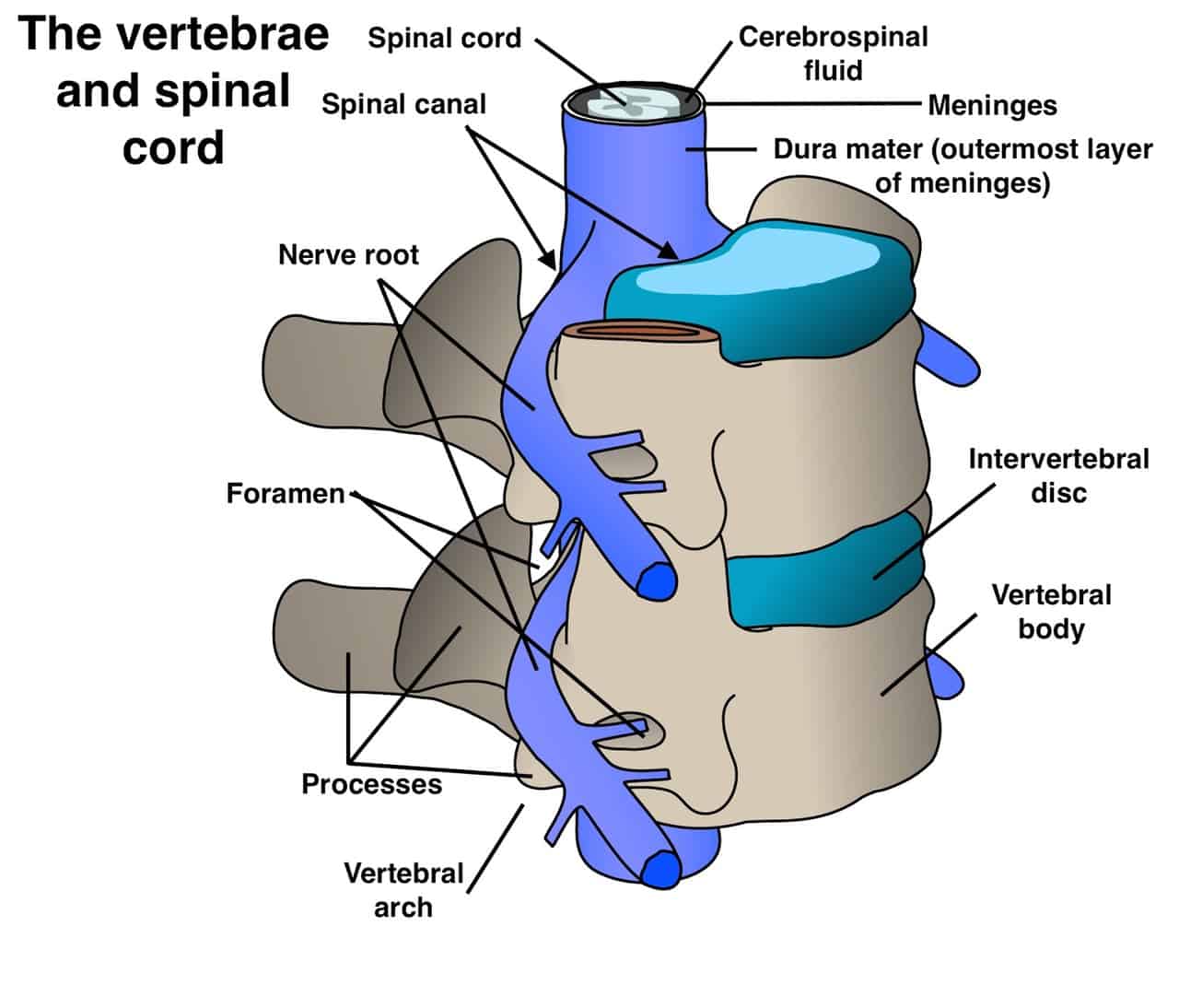

In the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine, all vertebrae are essentially similar. Each vertebra (the singular of vertebrae) is composed of two sections. One section, the vertebral body, is a solid, cylindrical segment, shaped something like a marshmallow. It faces the front of the body (look again at the diagram above) and it provides strength and stability to the spine. In the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine, all vertebrae are essentially similar. Each vertebra (the singular of vertebrae) is composed of two sections. One section, the vertebral body, is a solid, cylindrical segment, shaped something like a marshmallow. It faces the front of the body (look again at the diagram above) and it provides strength and stability to the spine.

The other segment is an arch-shaped section of bone called the vertebral arch. Projecting from the back of the vertebral arch are segments of bones, called processes, that provide attachment points for muscles, ligaments and tendons. These processes face the back of the body, and you can feel some of them if you use your fingertips to press the skin in the center of your back.

The vertebral arch is connected to the vertebral body by two small columns of bone called the pedicles. Sections of bone called the laminae form the “roof” of the arch. A hollow space like the center of a ring is enclosed by the vertebral body, the pedicles, and the laminae. Stacked on top of one another in the spinal column, the rings align to form a long, well-protected channel known as the spinal canal.

Inside the well-protected spinal canal is the spinal cord, the delicate bundle of nerves and other tissue that connects brain and body. Membranes called the meninges cover the spinal cord. The meninges hold in a fluid called cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that bathes and cushions the spinal cord. (See below for diagram of spinal cord, cerebrospinal fluid, and meninges.)

The spinal canal also houses the beginning of the spinal nerve roots. These are the nerves that leave the spine, exiting the spinal canal through foramina (small openings) to branch out to the body.

The cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine have the same overall anatomy in adults and in children. The sacral spine is a special case; it is markedly different in pediatric and adult patients. At birth, the five sacral vertebrae resemble the vertebrae in the lumbar spine just above them. Late in the first year of life, areas in and around these vertebrae begin to ossify, or form bone, and the shape of the vertebrae begins to change. Around the time of puberty, the five sacral vertebrae begin to fuse, and by the mid-twenties to mid-thirties, they form one solid bone.

Surgical treatment, in adults or children, is often required for one or more of the following reasons:

Decompression of the spinal cord or nerve roots: Pressure on the spinal cord or nerve roots is called compression; removing that pressure is called decompression. Compression of an individual nerve root can inflame and irritate it, causing pain, weakness, or sensory changes in the area of the body served by that nerve root. (Usually this is in a single arm or leg.) Compression of the spinal cord can cause pain, weakness, or sensory changes in both arms or both legs; loss of bowel or bladder control; and permanent injury. Laminectomy, corpectomy, and discectomy are examples of decompression surgeries.

- Removal of a tumor or vascular malformation: Tumors and vascular malformations are surgically treated with microsurgical tumor removal, in which the neurosurgeon uses an operating microscope and very fine surgical tools to remove the tumor or malformation.

- Restoration of spinal alignment and stability: Many conditions, traumas, and some surgical treatments, can cause the spine to lose its proper alignment and stability. Neurosurgeons may use surgical treatments such as osteotomy, pedicle subtraction osteotomy, or vertebral column resection to realign the spine. Surgical treatments like instrumented spinal fusion can restore the spine’s strength and stability.

|

| Preparing for Your Appointment | At The Spine Hospital at The Neurological Institute of New York, our neurosurgeons want you to feel as prepared as possible for your surgery. We want to make sure you understand the goals of your procedure, as well as what you can expect following the surgery.

The information on this site can help you understand your condition, its general surgical treatment, and how to prepare for surgery in general. For example: make a list of your medications and allergies for your doctor; do not wear nail polish or makeup on the day of surgery. But your neurosurgeon is the very best resource for helping you understand the ins and outs of your individual case, so use your time with him or her at your appointment to ask questions. Some patients find it helpful to write down questions as they think of them, and bring those lists of questions to their appointments.

The world-class neurosurgeons at The Spine Hospital at The Neurological Institute of New York continue a long tradition of skill, care, and expertise that result in the best possible surgical outcomes for our patients. Drs. Paul C. McCormick, Michael G. Kaiser, Peter D. Angevine, Alfred T. Ogden, Christopher E. Mandigo, Patrick C. Reid and Richard C.E. Anderson (Pediatric) are experts in surgical spine treatments.

|

In the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine, all vertebrae are essentially similar. Each

In the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine, all vertebrae are essentially similar. Each